What would Gameboy have been without Tetris, Wii without Wiifit, and Windows without its Office suite and Facebook without its instant messenger? Each platform has built its success around one application, the killer app, the one which in and of itself justified the purchase or adoption of the platform. Where are the killer apps born from open data? Behind this persistent question, one continually repeated from the outset of the movement, lies a deep misunderstanding regarding the true value of open data. It is as if the open data business model only exists in the creation of revolutionary mobile applications.

“This article is an excerpt of the book Open models published in French in 2014 and translated in 2016”

Let’s gladly admit that we are to blame – this biased vision is in fact partly due to the open data players themselves. In order to facilitate education, they set out to describe a one-way model, which would naturally flow from data producer to mobile application developers who reuse these data.

Yet with hindsight, and a few years of maturity later, it is now easy to see that economic viability of mobile applications is more often the exception than the rule. Also, that open data business models are most often found in service platforms which facilitate the meeting of producers and reusers of open data.

This model is definitely less attractive than the promise of the killer application. But it is also infinitely more robust and realistic. We will now explore the basis for this model.

Redefining the “value” of data: from stock to flows

As an intangible non-rival good that can be endlessly duplicated, data does not have a real value in and of itself. If a developer or a data center consumes an extra datum, this usage will not mean that one additional unit will be deleted. Quite the contrary in fact. The reuse of a datum creates new data – the renowned “metadata”.

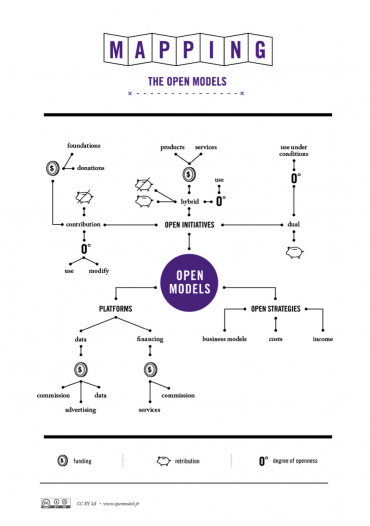

The value of data is thus multiplied in the flows and exchanges rather than in stock and accumulation. Logically, it is from the orchestration of these flows that new open data intermediaries position their business models.

The rising power of intermediaries

The fantasy of the open data killer app is based on a simplistic vision of the data producer/consumer relationship and of the nature the flow that unites them. It leads one to believe that this is a one way and unilateral flow between two parties, completely obscuring the technical foundation that conditions reuse. Yet this intermediary link is increasingly needed in the value chain. These service platforms that position themselves between the producer and the reuser consolidate and accelerate the potential for open data innovation by simplifying access to, transformation and consumption of open data.

The value of data is thus multiplied in the flows and exchanges rather than in stock and accumulation

Even more so given that the economy of these intermediary platforms also provides a data producer with the opportunity to integrate the enriched, cross-referenced and transformed data for themselves. This is what we refer to as a “feedback loop”. The boundary between data producers and users thus becomes porous and blurred while at the same time the intermediary positions itself as a critical element in the ecosystem.

The prevalence of the freemium model – how to reconcile free data and platform economics?

Intermediary service platforms built from open data are oriented towards the producer and/or reuser. For the producer, they simplify publication and encourage use, in particular by working on the interoperability of formats. As a reuser, they offer a huge range of services which optimize data consumption (data standardization, API, cloud based hosting, customization, etc…)

Even though several business models coexist, it is the freemium model that leads the pack. This model is based on the combination of two offers – the first, free, offers users access to data with limited services. But as soon as the user wants to access the broader service offering, they have to subscribe to the paid offer. Moving from one level to another happens according to different functional criteria, such as the volume of data consumption, cloud storage or associated services which depend on the interface (for example API, customization or data science services).

In the freemium model, data is free whilst the service is paid. Why? Because the true cost of open data is found in the technical architecture that supports the positioning of intermediaries and facilitates the flow of data, their circulation, transformation and storage for constant reuse.

The boundary between data producers and users thus becomes porous and blurred

The freemium model is therefore perfectly adapted to the free culture of open data, but also to the technical architecture that makes scalability possible.

Let’s now try and define a more detailed typology of the different intermediary platforms that belong to this great big freemium family. Three categories can in fact be observed.

MapBox: freemium with diverse functionalities

MapBox is a map service provider built on open data from OpenStreetMap. The advantage of this service is that in addition to the raw OpenStreetMap data, it has an added layer of map design and tools (software development kit, map customization, API, cloud hosting, etc.) which allows development, hosting and a guarantee of scalability for maps published as web or mobile versions.

In addition to the free offer, several paid offers are available depending on the number of views on the maps (determined by API queries) and the storage volume in the MapBox data centers. In this model, the user pays for the consumption of the technical architecture.

OpenCorporates: freemium based on the purpose of use

OpenCorporates is a British start up, incubated at the Open Data Institute, centralizing the public information of over 77 million companies worldwide. This service offers an API which enables navigation of these data (address, accounting information, etc.) and to perform analyses by sector.

In order to avoid the privatization of open data after they are processed, OpenCorporates uses a model based on purpose rather than consumption. This means that access to data is free for projects that respect the share-alike principle by enriching the open data of OpenCorporates and keeping them open. On the other hand, if the project involves a plan to close data in the context of a commercial license, once their use, cross-referencing and enrichment is over, the service becomes paid.

OpenCorporate includes the double license principle that is treasured by open source. As Jeni Tennison, Chief Technical Officer of the Open Data Institute highlighted, this model can be adapted according to the turnover or market share of the reuser.

Enigma.io: freemium as a Trojan horse

Enigma.io is an open data research and consumption platform. Enigma.io obtains data from American federal agencies and companies. The platform currently distributes more public data than the American government itself, whether it is for visa approvals, previous fire records or even cargo present in the Port of New York. Enigma.io thus offers access to structured data sets underpinned by other associated services (facilitated and targeted search, access by API, etc.).

Enigma.io goes even further by using the freemium as a window into its data science know-how in order to offer ad hoc services that are not directly related to the platform. In this case, the freemium is in reality acting as a Trojan horse. It is a powerful demonstration of the skills of a team that sells its data analysis skills by targeting specific market segments. This is the case in the insurance sector where Enigma.io offers to create a model and anticipate risks based on previous fire records data compiled on the platform.

If other models could have been introduced, the prevalence of the freemium model and its ingenious ability to reconcile free data and the sale of a service make it an excellent indicator of the real “value” of open data, that which is found in the flow rather than in the stock.

As early as 2009, the author of Free: The Future of a Radical Price, Chris Anderson, showed that the presence of something free did not mean that there was an absence of business models, quite the opposite.

The abundance of data and immaterial goods in general creates a new scarcity in its wake

Even more so given that the abundance of data and immaterial goods in general creates a new scarcity in its wake, which is found not in the possession of the good but in the know-how acquired in its exploitation.

The organization of the flow, the harmonization of data sets and the creation of associated services such as data sciences, present themselves as viable business models. It is also perhaps an opportunity for data producers looking for business models to think up new offers, taking inspiration from the intermediaries formed from a “gap” in the chain between producers and reusers.

Translation by Nicola Savage